Surely, comrades, you don’t want Jones back?

Originally published: April 3, 2024

Unless introduced as a moral story in middle school, it is unlikely that anyone would have read Animal Farm

merely as a fairytale. It is only natural to explore the milieu of the writer, especially if critically acclaimed as in

this case, and the context in which he situated the story before picking up a classic. Such an attempt here

would reveal that it was a political satire that George Orwell wrote, taking a stab at the political environment in

Russia at the time. His attempt was much discouraged since the British media during the time, unquestioningly,

almost servilely, supported Russia and whatever it stood for; Russia was an ally to Britain in the war and was

strictly not to be upset. To give some context, the book was written by the end of 1943, but wasn’t published

till August 1945. What’s worse, the Russian viewpoint was supported and publicized uncritically, as it were,

even without the influence of the British government or any pressure groups. “At this moment what is

demanded by the prevailing orthodoxy is an uncritical admiration of Soviet Russia” Orwell wrote in his

proposed preface to Animal Farm, and “So long as the prestige of the USSR is not involved, the principle of

free speech has been reasonably well upheld.”

Animal Farm is a story of rebellion, more precisely, a rebellion gone wrong. It chronicles the struggle where

people—in this case animals—subvert the existing order, feeling exploited, in the hope of a better tomorrow

that the much-sought self-rule promises. It describes with great genius and detail how the rule that the citizens

placed their hopes in turns against them. The story is an account of unrest, hope, and disappointment that is

realized through it all, yet of a nature that may not be an end in itself, but a new point of departure.

The story opens with a wise old boar gathering all the animals of the Manor Farm after their master retires for

the night, to describe to them an uncanny dream he had the previous night that led him to have a vision for his

fellow residents and their farm. He forebodes an uprising against human command, that reaped all the benefit

of the animals’ labour, leaving just enough produce for the working-animals to survive, not thrive, keeping the

rest for self-service and profit. The old pig breathes his last in a few days’ time, and the rebellion that he

prophesied with an uncertainty about its scheduled hour is realized not so long after his passing.

Since the revolutionary speaker had been a pig, the pigs take it upon themselves to secretly assemble the farm

in the dead of the night, and after one such meeting, the animals all rise up and mount a rebellion, coming

strongly out against their master, Mr. Jones, owner of the Manor Farm, resulting in his complete expulsion

from the premises. There are cheers and celebrations: the animals all exult in recognition that they are now the

masters of the farm they inhabit and work on—a realization that has gaps that won’t be felt until much later.

However, for now, sense is soon restored and in the wake of this newly found independence, they establish 7

commandments equivalent to a constitution of today’s democracies. The commandments are inscribed on the

wall—the pigs had educated themselves to read and write—and “would form an unalterable law by which all

animals on Animal Farm must live for ever after”. Each animal assumes a certain role in the farm machinery,

and pigs, being the only literate ones and having spearheaded the whole revolution declare themselves the

“minds” of the farm and resort to policymaking, expediently keeping themselves from any physical (real)

work.

Things go on fine for a while: the animals continue to work in coordination, more willing now to work in the

fields, content in the knowledge that none of the yields they raise is lost on any work-shy “master” or his lot,

but all comes back to them—that’s what they are made to believe, anyway. Apart from changing the name

from Manor to Animal Farm, they adopt a flag and an anthem—“Beasts of England”—in keeping with the

spirit of self-rule and their animal-led farm. Trouble isn’t felt until one of the two pig leaders, Napoleon,

becomes absolutely intolerable to the other pig leader, Snowball, whose approach towards the community and

civil affairs is often at variance with himself. He decides to do away with all dissidence: Snowball is declared

a traitor—despite formerly having been awarded for showing extraordinary valour in a freedom-jeopardising

combat—and is driven out. The pigs had been outslicking the farm animals even before this, but it is here that

manifest misadventures come knocking.

Things begin to crumble: from more labour and less food—despite the numbers suggesting otherwise—to the

commandments, the “unalterable law”, being discreetly doctored one after the other to foster the pigs’

indulgence. The dictate that originally read, “no animal shall sleep in a bed” for instance, is sheepishly edited

with the words, “with sheets” added in the end with the pigs extending over Mr. Jones’ residence above and

beyond using it as their policymaking chamber while the labouring animals subsist on the farm. The apples are

reserved for the pigs stating thatthey are absolutely essential for a pig’s health while the rest of the lot sustains

on low-quality supplies. The anthem “Beasts of England” is made obsolete, reasoning that it was the song of

revolution, and since it is the animals who now rule the farm with Comrade Napoleon painstakingly

overlooking everyone’s wellbeing, the revolution is hereby complete. Everyone’s wellbeing is “overlooked”

alright.

Before exploring what happens next, let us take a moment to see whether what’s happening in Russia under the

current regime is unlike what transpires in Orwell’s Animal Farm. The late opposition leader, Alexei Navalny,

to cite a much-known case. Isn’t it indicative of complete intolerance of any potential threat to the ruling

United Russia? Of course, this was an extremity, but suppression goes unchecked on less extreme, though not

subtle, levels too. According to a BBC documentary released in 2022, Novosibirsk counsellor, Sergei Boyko,

among others, was barred from elections for 5 years owing to his links to the then-jailed Navalny. With the

opposition suppressed, Russia is not just authoritarian—more jails, iron hand on dissent—but also nearly

totalitarian. On ballot papers, the voters seem to have a choice, but according to critics, these parties that

appear on the papers have been reviewed and “approved” by the Kremlin. As for Putin’s fiercest opposition

leaders, they’ve been kept at bay. Russian chess legend, Garry Kasparov, one of the most vocal critics of the

current Russian regime and President Vladimir Putin, was recently added to Russia’s state list of “terrorists and

extremists”.

Back at the Animal farm, those who are found to have links with the outcast leader, Snowball, are hanged on

the charges of treason by the reigning pig, Napoleon. The administration adopts various methods to suppress

any questions that may lead to dissent. The sheep had been trained to chant, “four legs good, two legs bad” to

signify that all animals were comrades—that’s what they had come to call each other after the revolution—and

all those who walked on two legs, the humans, were enemies. To chant this right after any new directive or

policy is introduced to drown out any questions or voices of dissent was the drill. Towards the end though,

when the pigs learn to balance themselves and walk on two legs—since it is clear by then that they had been

attempting to please and take up with the humans of the nearby farms—even the sheep’s mantra is acclimatised

to parroting, “four legs good, two legs better.”

“Surely, comrades, you don’t want Jones back?” Napoleon’s mouthpiece repeats to the farm animals to press

them to slog against barely any food or rest, though whether they ate as much as they had under Jones’ rule or

less is now hard to say: Jones and his time is a distant memory, so much so that the new generation of animals

on the farm know nothing of him, and are educated—under Napoleon’s direct watch, of course—only of their

Comrade’s great achievements and the good he did to the citizenry.

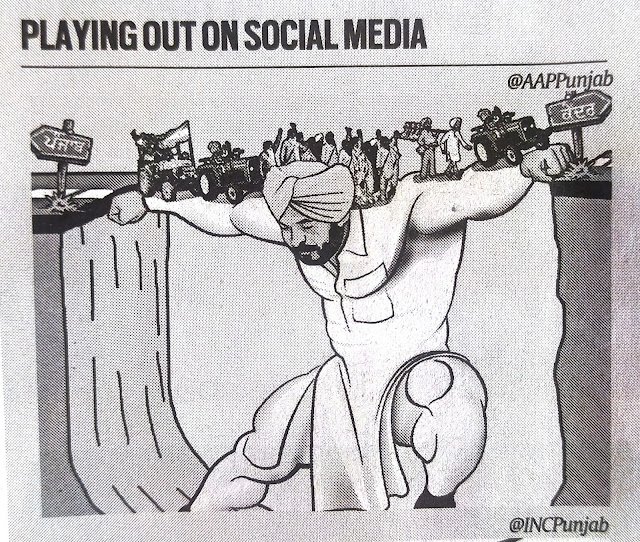

In India, having a staunch opposition, giving us options to change the government, is quite a distant image too.

Besides lack of grit and strong leadership in the Opposition bloc, competition to the reigning administration

has been systematically destroyed by means of encouraging defections and poaching leaders from political

adversary-camps in the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections, not to mention disrupting the mechanics of state

governments using Governors. As though that wasn’t enough, they have fallen to scuttling the Opposition’s

finances and finally, enforcing party arrests. Such occurrences do not materialise in the BJP-ruled states. The

leadership playing fast and loose, leaving the Opposition bloc in a shambles, is depriving us of electoral

options at best. All power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely. With only one perceptible player to

ascend the throne, what are we if not monocratic? They say, “it’s better to have it and not need it than to need it

and not have it”, particularly when “it” is the available choices for citizens in the matter of power contention.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm ends amidst perplexity, rendering the working-class animals forlorn. However,

with an open end, the story may go in any direction: there could be yet another rebellion, or there could be

eternal servility and exploitation. History suggests that no norm is permanent whatever the case, so when the

prevailing order will subvert—it’s for the audience to decide after they put the book down.